Editor’s Note: This blog post is co-authored by Cathy Day, PhD, NSAC Climate Policy Coordinator and Michael Happ, Program Associate for Climate and Rural Communities at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, (IATP). ITAP is an NSAC member organization with a 30-year history of pursuing cutting edge solutions that benefit family farmers, rural communities and the planet.

Overview

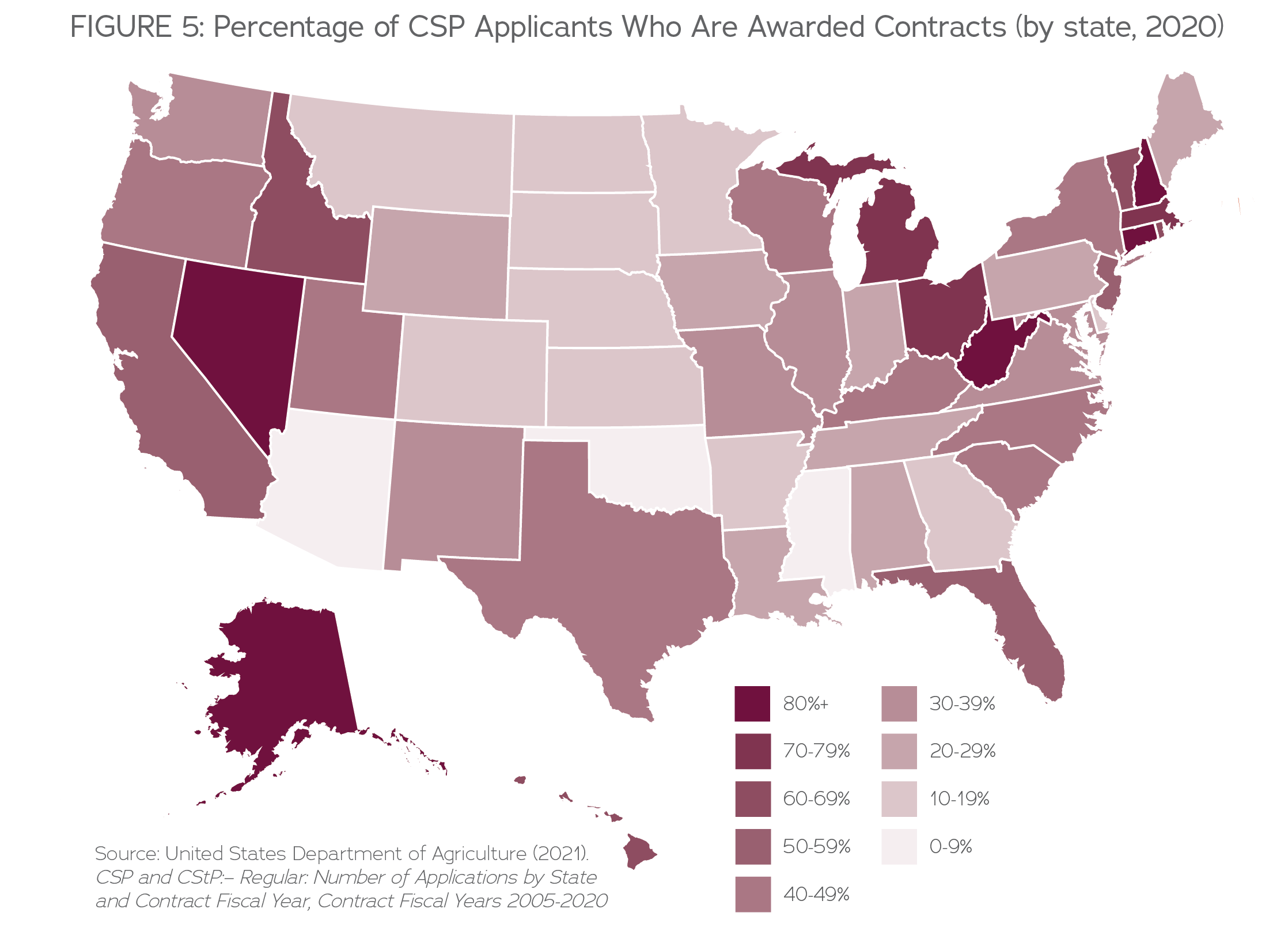

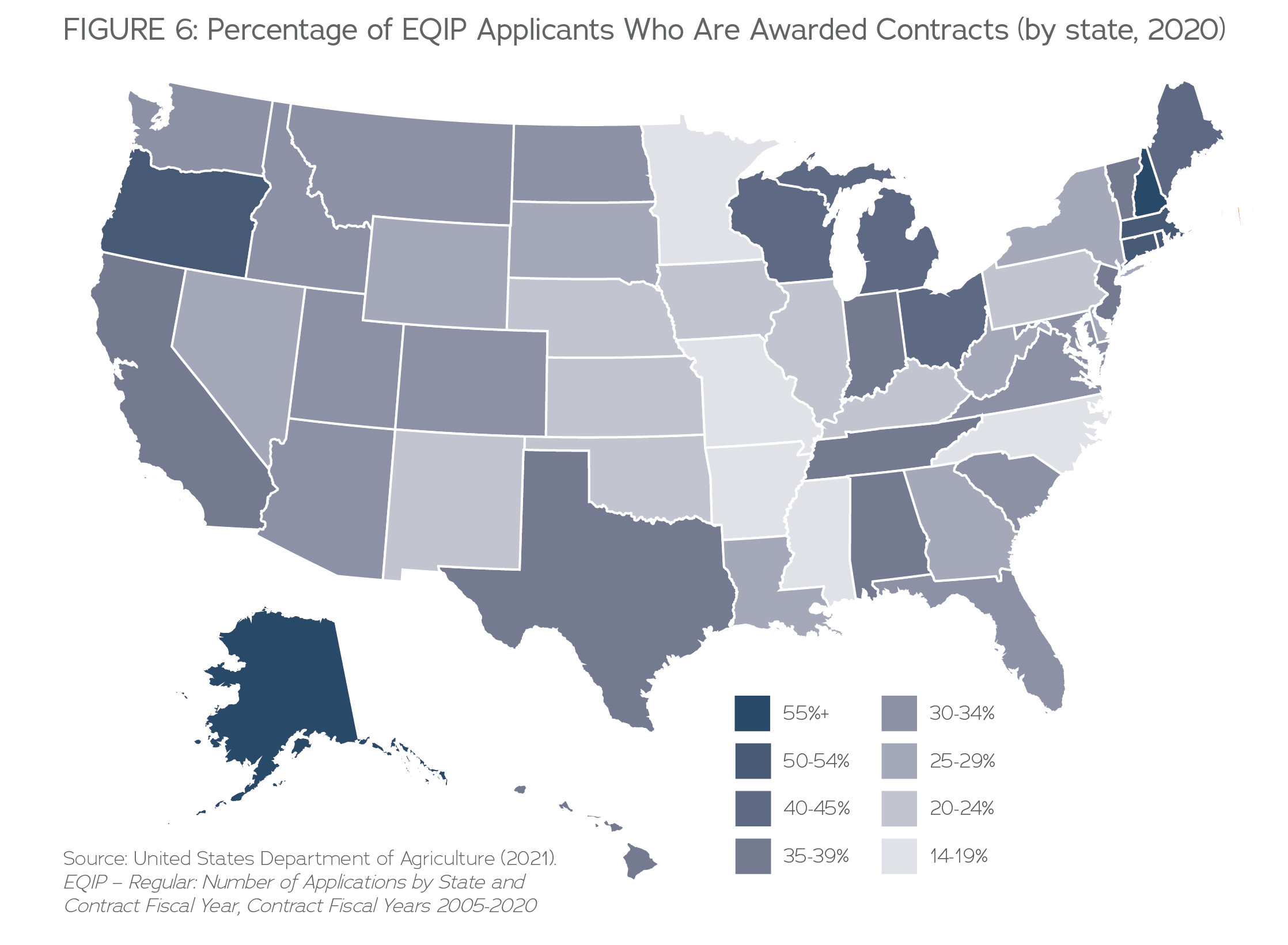

According to data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), between 2010 and 2020, just 31% of farmers[1] who applied to the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and only 42% of farmers[2] who applied to the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) nationwide were awarded contracts. Over the span of 10 years, EQIP turned down 946,459 contracts and CSP denied 146,425 contracts, at least partially for lack of funds. These numbers vary widely by state, but some of the lowest approval rates occurred in major agriculture states. The whole farm approach supported by CSP and the practices supported by EQIP help farmers reduce greenhouse gas emissions, sequester carbon, and adapt to emerging and extreme climate-related changes. Right now, Congress has a unique opportunity in the budget reconciliation process, and later in the next Farm Bill, to dramatically increase spending for CSP and EQIP, which would have an immediate, tangible impact on farmers’ ability to respond to the climate crisis.

Context

In the wake of the International Governmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Report,[3] it is clearer than ever that governments must use every tool at their disposal to address the climate crisis. The IPCC’s report underscores the sobering reality that there are currently enough greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to disrupt our planet for centuries, and we have a short window of time to reduce our emissions drastically.

This IPCC report was released as Congress is debating new investments that respond to the climate crisis within budget reconciliation, a process expected to add $3.5 trillion in new spending. Through the process of budget reconciliation, federal policy can be passed with only a majority of votes in the U.S. Senate, avoiding the need for 60 senators’ support and any opposing filibuster.[4] NSAC and IATP advocate for a bold, climate-focused agriculture title in the budget reconciliation process. Such a budget could transform the landscape for farmers, particularly those who have been closed out of popular conservation programs that can play an important role in responding to the climate crisis. The budget could be a once-in-a-lifetime solution for the crisis of our lifetime.

Farmers are often on the front lines of climate change. While climate change affects everyone’s livelihoods, it does so for farmers in an immediate, visceral way. Whether it is through droughts, floods, extreme heat, megafires or any other weather extremes, climate change can ruin a crop or devastate animals in the blink of an eye. According to experts at USDA’s Economic Research Service, climate change is expected to increase the cost of the federal crop insurance program from 3- 20% or more, depending on how quickly we respond to the climate crisis.[5]

When confronted with the enormity of the climate crisis, some activists and policymakers instinctively suggest new programs. Many of these ideas have merit but will take some time to hit their stride. Fortunately for farmers, we already have two successful but under-funded programs in place to support farm transformations and increase climate resilience: The Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) and the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP).

Each year, farmers apply for CSP and EQIP contracts that support practices that protect the soil, air, water and wildlife. These programs can also help farmers transform their farm practices to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, sequester carbon, and reduce farm vulnerability to climate-related disruptions like increased (or decreased) rainfall, warmer temperatures, invasive plant species and others. Farmers need help recovering from climate disasters, but they are far better served when programs like CSP and EQIP support long-term, permanent changes in practice that reduce the impact of future system disruptions–whether from climate change, pandemic, or economic upheaval.

The Natural Resource Conservation Service generally categorizes eligible practices under categories such as soil health, nutrient management, grazing/pasture, agroforestry and sometimes to crop-specific practices like rice. It is under this general structure that EQIP’s new “Climate-Smart Agriculture and Forestry” pilot program is organized.[6] While the practices outlined in the pilot program already exist in EQIP and CSP, NRCS is aiming to make it easier for climate-conscious farmers to recognize which kinds of practices fit with their operation. Despite good intentions, some of this money, and EQIP resources in general, is misdirected. For example, anaerobic digesters for large-scale concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) are listed as a climate-smart practice. CAFOs represent inherently unsustainable forms of agriculture, with high greenhouse gas emissions combined with other negative environmental impacts like water and air pollution. The use of digesters to treat large amounts of animal waste is a band-aid on the much larger problem of CAFO greenhouse gas impact. Although the methane they produce is generally burned for energy, partially reducing its potent greenhouse gas impacts, the burning also releases other forms of air pollution including sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and carbon monoxide. In addition to causing localized air pollution, all of these gases also have their own indirect greenhouse gas effects.[7] In supporting these digesters, the new EQIP pilot program supports a model of agriculture that is actively making the climate crisis worse by supporting a form of agriculture that relies on high inputs of greenhouse-gas-producing synthetic chemicals..

Why are CSP and EQIP Important?

EQIP and CSP are both intended to help farmers pay for environmental improvements on their farm. EQIP payments are intended for small, one-off projects like planting grass seed in waterways to prevent erosion, whereas CSP is intended to help pay for whole-farm projects, bundling projects together for broader aims like erosion control, water quality or wildlife habitat enhancement.

Traditionally, EQIP has provided cost share assistance for targeted conservation projects on farms. Many of these practices, like buffer strips, multi-story cropping, wetland enhancement and others can help mitigate some of the effects of climate change for farmers, acting as sort of an agroecological insurance against extreme weather events.

While EQIP can pay for beneficial practices, it is not a perfect program. On top of sending millions of dollars every year to CAFOs, in recent years, EQIP has also been used as a tool to weaken CSP. During the Trump administration especially, USDA leadership aimed to reduce the differences between the programs and introduce more first-time conservationists to CSP, even though it is meant to be used to help experienced conservationists build on past successes, or for those whose on-farm needs go beyond what EQIP can provide.

Climate-focused farmers are perfect candidates for the whole-farm-focused CSP. Whole-farm CSP allows for technical assistance on farm planning with which farmers can potentially design systems that may reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, increase their carbon sequestration, and decrease their vulnerability to climate impacts. However, such farmers are now often diverted to EQIP’s less comprehensive new pilot program, or even to the broader EQIP program. This could be because in many locations EQIP is more well-known among farmers and USDA staff, or that it is a simpler program to administer.

CSP is traditionally considered the next step for EQIP contract holders. While EQIP is considered a “one-and-done” cost share program, CSP is meant to work with farmers to implement larger conservation goals on their farm. Among these goals are cropland soil health/sustainability, fish and wildlife habitat, water quality and grazing land conservation.

If an operator wants maximum water conservation across their farm, CSP helps them decide which specific practices working in concert with each other can best achieve that goal. For one farmer that could mean planting grassed waterways, grassed buffers along a creek, and rotational grazing and fencing to limit the amount of time livestock might be in a body of water, minimizing contamination risk.

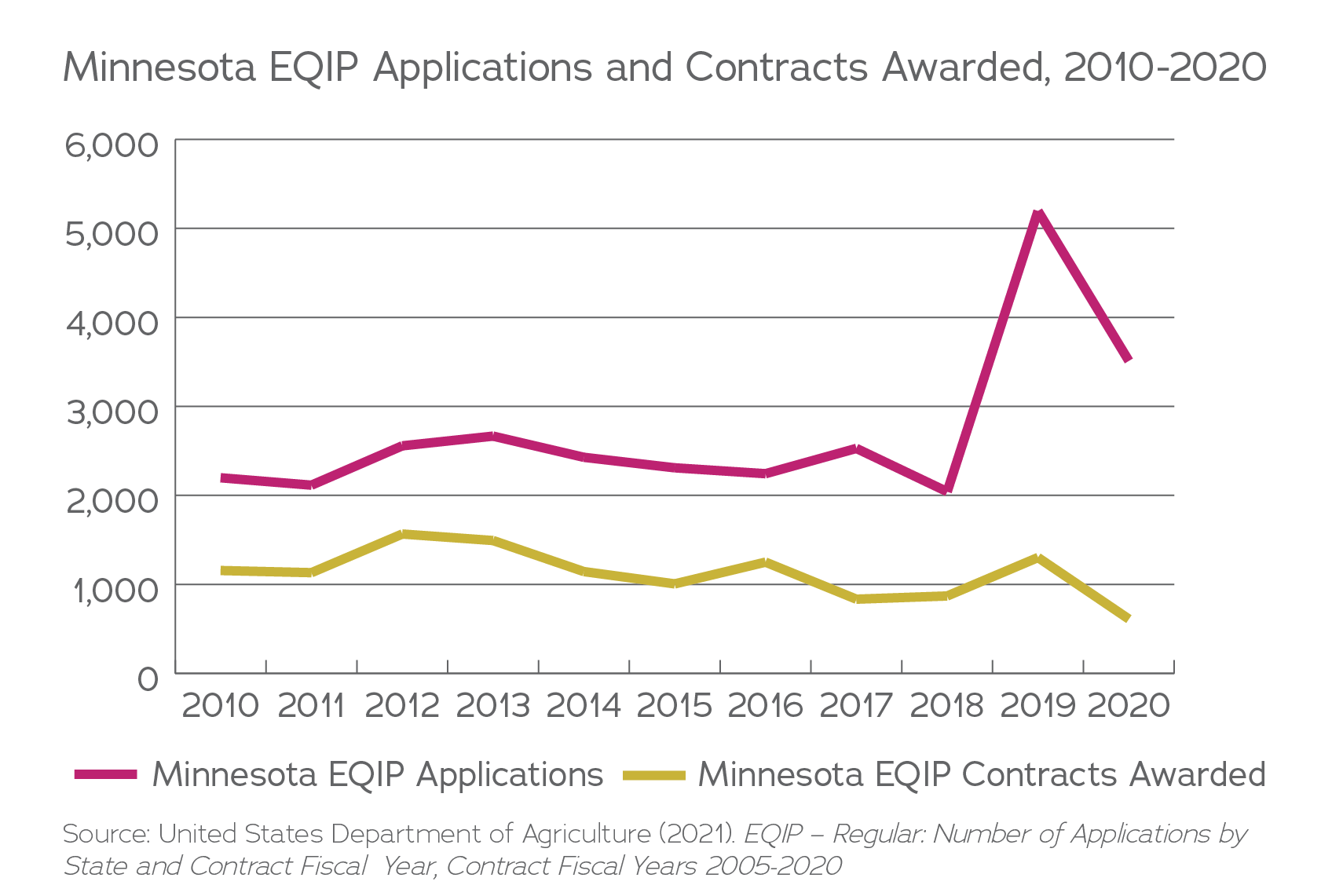

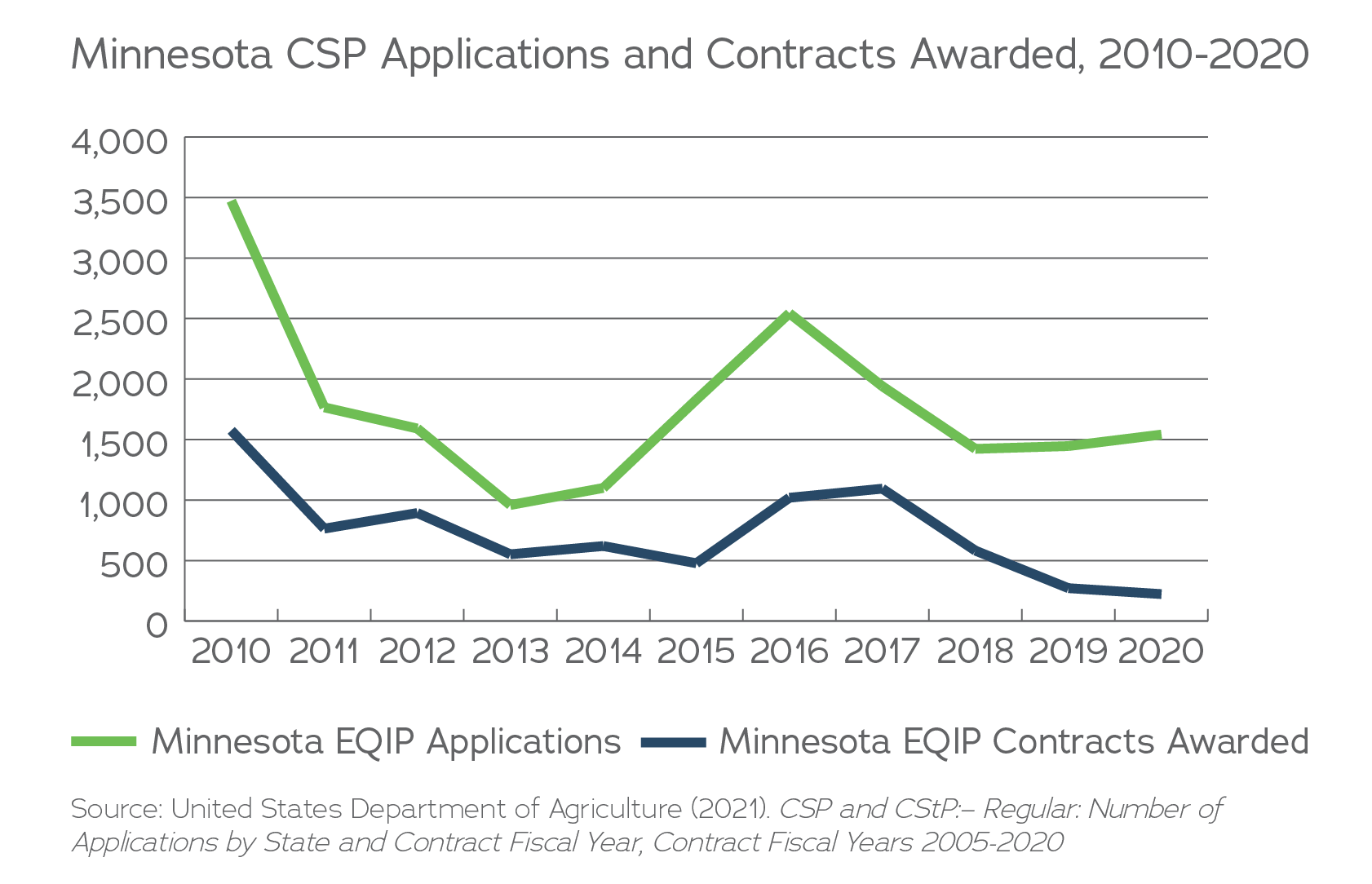

The Case of Minnesota

Over the past 15 years, Minnesota has awarded more CSP contracts than any other state, with a total of 8,661 contracts between 2005 and 2020. Despite this record of success, in 2020 Minnesota only awarded contracts to 14% of those who applied, landing it 47th out of 52 states and territories. With more designated resources, Minnesota could award more contracts, conserve more acres and help more farmers.

Similar to its relationship with CSP, Minnesota has awarded thousands of EQIP contracts over the past 15 years, making it a well-known program among farmers and contributing to its popularity. However, Minnesota does not award EQIP contracts to many of its applicants, saying yes to just 611 contracts in 2020 across the state, or 17% of the total applicant pool. That ranks Minnesota 50th out of 52 states and territories in successful applicants.

Many of the goals EQIP and CSP set out to achieve have secondary climate mitigation benefits, helping farms bounce back from climate change-related setbacks. For some, the climate benefit can be more direct. For those looking to transition from carbon-intensive, concentrated livestock operations to pasture-based livestock, CSP and EQIP can both be great tools, helping pay for fencing for rotational grazing, healthy forage, and other ways to make the most out of pastureland without stressing it to the breaking point.

Access to Conservation Programs for Farmers of Color

Five percent of CSP contracts are set aside each year for “socially disadvantaged farmers,” the USDA term for farmers of color. These set-asides are pools where the applications for farmers of color are only ranked against each other rather than in the general pool with all other farmers. Though this set-aside is intended to improve access to conservation programs for farmers of color, there is a long and painful history of discrimination at NRCS, and at USDA more broadly.[8] This history has impeded outreach and signup processes.

The data that exists on farmers of color at USDA can be confusing or misleading. Part of the reason is that data is not broken down by race at the state level (with the exception of Hispanic producers), only by whether or not a farmer is classified as “socially disadvantaged.”

In addition, according to recent reporting by The Counter, discrimination in administering financial assistance to farmers of color continues into the current day, with data being distorted or misreported during the Obama administration and beyond to paint a sunnier picture than the reality at USDA.[9]

Despite the areas where USDA’s data falls short, the data that does exist can be helpful. The department recently made much of their data public in a dashboard-style format. This includes data on CSP contracts by race nationwide, which can be found here. Similar data for EQIP can be found here. In 2020, for example, only 245 CSP contracts and 2,158 EQIP contracts were awarded to farmers of color nationwide. That comes out to 3.7% of CSP contracts and 6.4% of EQIP contracts nationwide being awarded to farmers of color. According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, in 2017 there were over 240,000 farmers of color in the United States. While IATP was not able to determine how many farmers of color applied for CSP and EQIP funding, it is clear that when only 1% of farmers of color are enrolled in the largest conservation programs in the country, more needs to be done to support farmers of color, who are in many cases the most susceptible to climate risks.

What is happening with EQIP and CSP funding?

Since the inception of EQIP and CSP, there have been thousands more applications than contracts awarded. By nature of application-based programs, there will be those who are successful and those who are not. However, with the sheer numbers of rejections occurring and the trends over the last decade, we know that qualified applicants are being turned away and that lack of funding is a serious and growing issue.

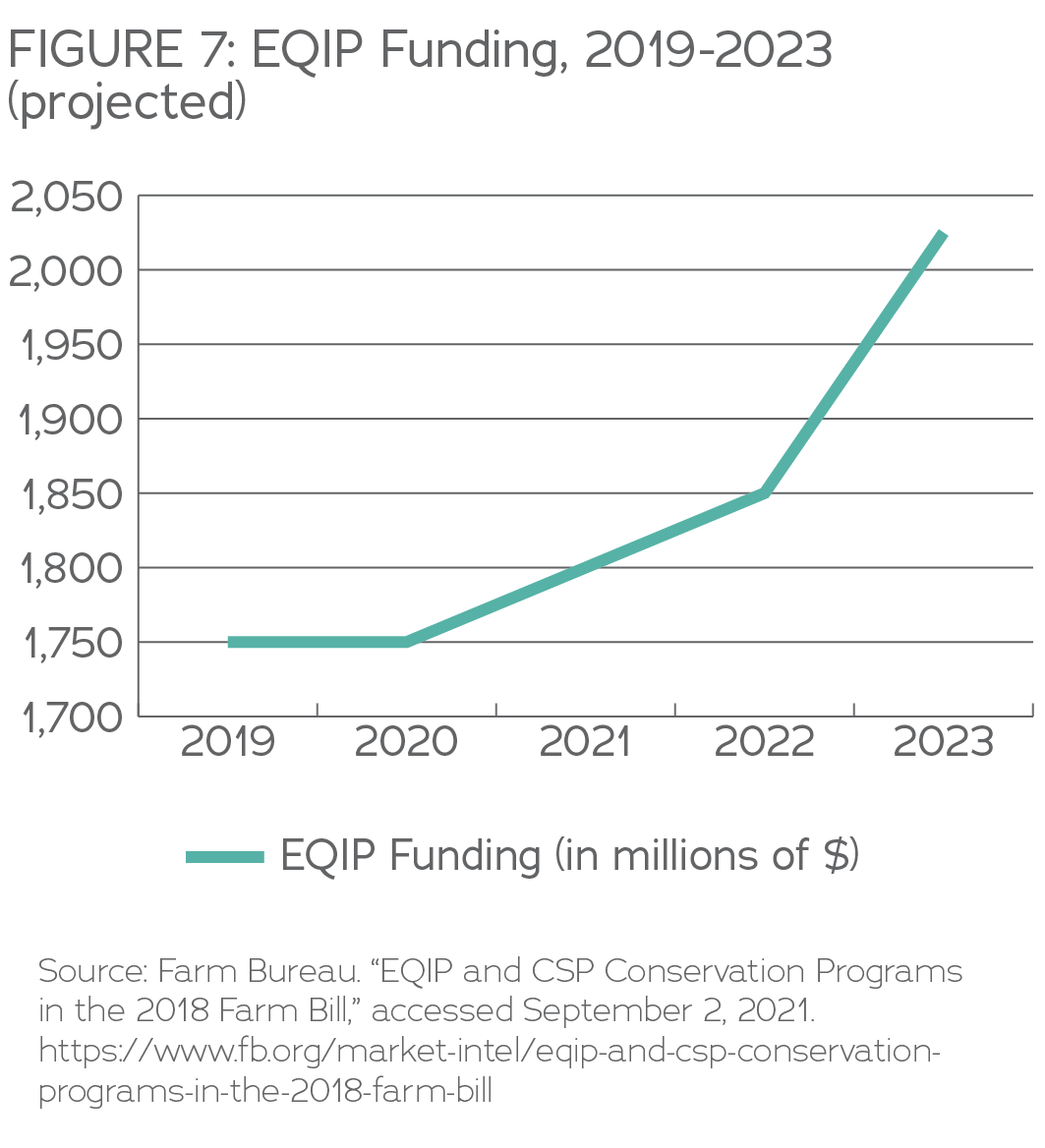

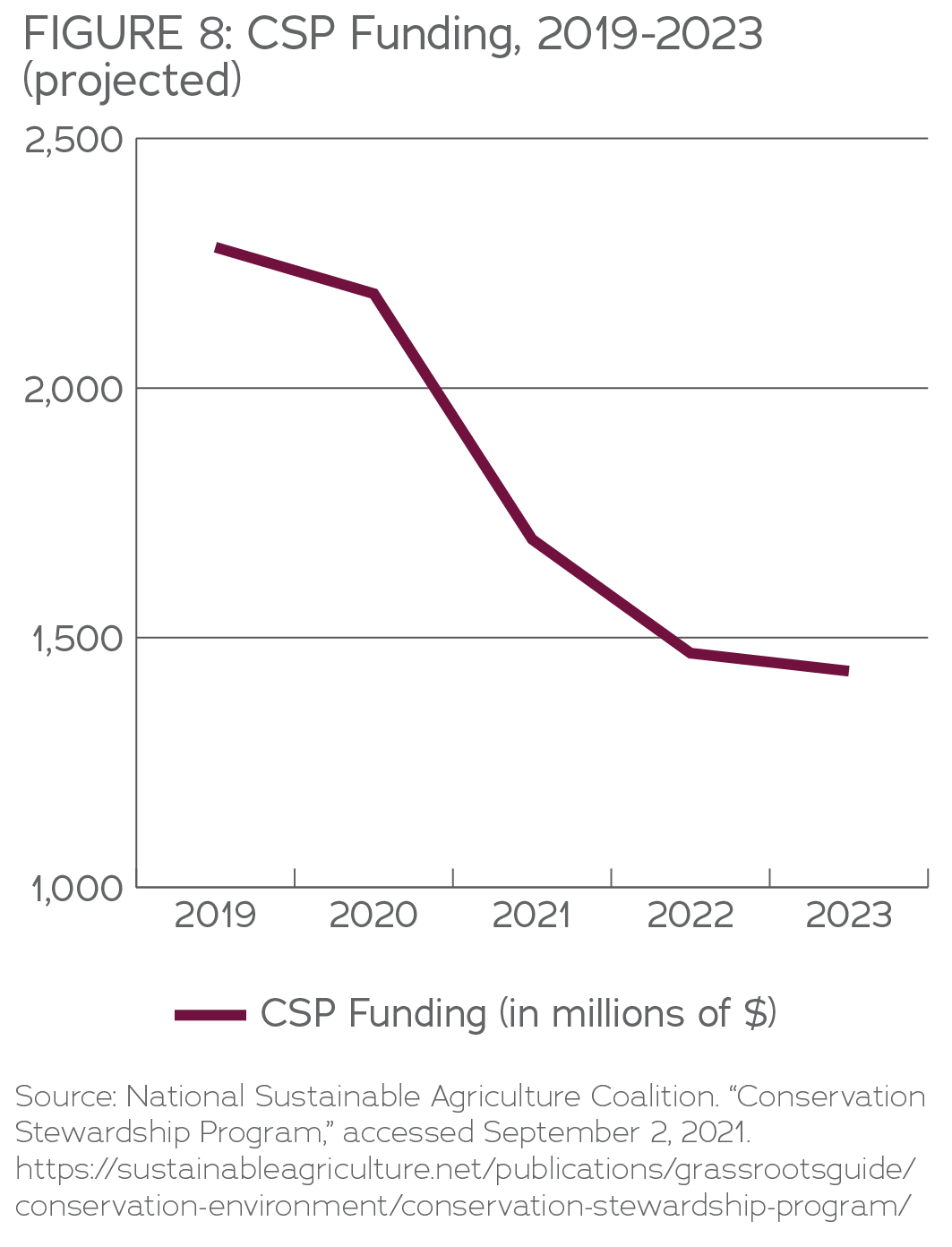

Below are two graphs showing a divergent path for the two conservation programs. As a result of the 2018 Farm Bill, CSP funding has been on a downward funding trend, with nationwide funding for the program as high as $2.3 billion in 2019, with projected program funding to decrease to $1.4 billion in 2023.[10] At the same time that Congress decided to gradually cut CSP, it upped funding for EQIP, with the yearly allocation rising by $200 million between 2019 and 2023.[11]

This is a dangerous trend, considering that CSP is meant to be a more comprehensive program than EQIP, having a higher potential conservation benefit and financial benefit to farmers. This trend coincides with a long-term shortage of NRCS staff, reducing technical assistance capacity for the more paperwork-intensive CSP.[12]

A Unique Opportunity to Support Farmers and Protect the Climate

Expanding resources for CSP and EQIP are certainly not the only tools our food and farm system needs to respond to the climate crisis. However, these programs can work in concert with other climate action policies, including stronger regulations on agriculture’s major sources of emissions (dairy and hog CAFOs and synthetic fertilizers), reforms to commodity and insurance programs in the Farm Bill to support climate resilience, and deeper investments to support small and mid-sized producers contributing to local food systems.

What does this data mean for the immediate budget reconciliation process and the next Farm Bill? Perhaps the biggest takeaway is that there is intense demand for EQIP and CSP across the country, and that demand is not being met. There are some simple solutions to address this demand, some of which could be done without legislation. Other more lasting changes can be addressed now through budget reconciliation, and perhaps later through the 2023 Farm Bill.

Solutions Needed from USDA

- Clarify and reform the application process through Conservation Assessment Ranking Tool (CART), better supporting existing conservation measures while increasing transparency

- Ensure that CSP remains a whole-farm program and EQIP remains targeted for single conservation projects

- Meaningfully invest in CSP and EQIP outreach to farmers of color, and increase CSP and EQIP set-asides for farmers of color

- Prioritize the climate mitigation benefits of CSP

Solutions Needed from Congress

- Include an additional $30 billion for CSP and EQIP in budget reconciliation

- Authorize and appropriate more money for conservation technical assistance at NRCS

- Prohibit EQIP dollars from going to new or expanding CAFOs

Conclusion

What would U.S. climate policy look like if we had climate friendly programs that farmers trusted and applied for in droves? The good news is that these programs already exist: The Conservation Stewardship Program and the Environmental Quality Incentives Program. The bad news is that not nearly enough farmers are being awarded contracts to meet existing demand. When fewer than half of program applicants nationwide are awarded contracts (and in many agriculture states fewer than 20%), more resources are needed. These programs can go a long way toward helping farmers and rural communities bounce back from climate change-fueled disasters. If resilience was the only benefit of these programs, they might already be worth it. However, more farmers enrolled in these programs also means more financial stability for farmers, better soil and water conservation, more resilient local food systems, lower vulnerability to future disasters, fewer greenhouse gas emissions,and more carbon sequestration. Expanding access to these programs is low hanging fruit for Congress that can bring immediate benefits for farmers and the climate.

Appendix

Table 1: States Ranked by Percentage of 2020 CSP Applicants

Awarded Contracts

| Rank | State | 2020 CSP Applications | 2020 CSP Contracts | % of Applicants Awarded Contracts |

| 1 | Alaska | 2 | 2 | 100% |

| 2 | Caribbean Area | 12 | 10 | 83% |

| 3 | Nevada | 27 | 22 | 81% |

| 4 | West Virginia | 109 | 88 | 81% |

| 5 | Connecticut | 5 | 4 | 80% |

| 6 | New Hampshire | 15 | 12 | 80% |

| 7 | Massachusetts | 52 | 39 | 75% |

| 8 | Ohio | 200 | 147 | 74% |

| 9 | Michigan | 528 | 387 | 73% |

| 10 | Vermont | 54 | 37 | 69% |

| 11 | Hawaii | 29 | 18 | 62% |

| 12 | Rhode Island | 39 | 24 | 62% |

| 13 | Idaho | 94 | 57 | 61% |

| 14 | Florida | 92 | 52 | 57% |

| 15 | New Jersey | 9 | 5 | 56% |

| 16 | California | 208 | 109 | 52% |

| 17 | Pacific Basin | 32 | 15 | 47% |

| 18 | North Carolina | 340 | 157 | 46% |

| 19 | New York | 190 | 86 | 45% |

| 20 | Wisconsin | 1,176 | 532 | 45% |

| 21 | Utah | 124 | 53 | 43% |

| 22 | Texas | 610 | 256 | 42% |

| 23 | Oregon | 338 | 140 | 41% |

| 24 | Kentucky | 563 | 230 | 41% |

| 25 | South Carolina | 511 | 202 | 40% |

| 26 | Maryland | 66 | 24 | 36% |

| 27 | Illinois | 1,245 | 428 | 34% |

| 28 | Washington | 251 | 80 | 32% |

| 29 | New Mexico | 232 | 73 | 31% |

| 30 | Virginia | 431 | 135 | 31% |

| 31 | Missouri | 1,608 | 490 | 30% |

| 32 | Indiana | 372 | 103 | 28% |

| 33 | Pennsylvania | 534 | 144 | 27% |

| 34 | Wyoming | 34 | 9 | 26% |

| 35 | Maine | 12 | 3 | 25% |

| 36 | Louisiana | 706 | 173 | 25% |

| 37 | Alabama | 474 | 114 | 24% |

| 38 | Tennessee | 845 | 189 | 22% |

| 39 | Iowa | 1,442 | 300 | 21% |

| 40 | Delaware | 26 | 5 | 19% |

| 41 | Georgia | 1,332 | 250 | 19% |

| 42 | Kansas | 555 | 98 | 18% |

| 43 | Nebraska | 1,310 | 223 | 17% |

| 44 | South Dakota | 1,313 | 219 | 17% |

| 45 | Arkansas | 1,441 | 224 | 16% |

| 46 | Colorado | 321 | 47 | 15% |

| 47 | Minnesota | 1,541 | 223 | 14% |

| 48 | North Dakota | 848 | 122 | 14% |

| 49 | Montana | 670 | 85 | 13% |

| 50 | Oklahoma | 1,190 | 76 | 6% |

| 51 | Mississippi | 2,872 | 157 | 5% |

| 52 | Arizona | 80 | 4 | 5% |

TABLE 2: States Ranked by Percentage of 2020 EQIP Applicants

Awarded Contracts

| Rank | State | 2020 EQIP Apps | 2020 EQIP Contracts | Percentage Awarded |

| 1 | Alaska | 116 | 72 | 62% |

| 2 | New Hampshire | 365 | 207 | 57% |

| 3 | Massachusetts | 405 | 208 | 51% |

| 4 | Oregon | 1,162 | 591 | 51% |

| 5 | Connecticut | 160 | 81 | 51% |

| 6 | Rhode Island | 212 | 105 | 50% |

| 7 | Michigan | 2,445 | 1,059 | 43% |

| 8 | Maine | 1,173 | 498 | 42% |

| 9 | Ohio | 2,899 | 1,214 | 42% |

| 10 | Wisconsin | 3,635 | 1,436 | 40% |

| 11 | New Jersey | 610 | 227 | 37% |

| 12 | Hawaii | 312 | 116 | 37% |

| 13 | Vermont | 865 | 314 | 36% |

| 14 | Alabama | 3,849 | 1,379 | 36% |

| 15 | Indiana | 2,712 | 958 | 35% |

| 16 | California | 4,244 | 1,473 | 35% |

| 17 | Texas | 8,620 | 2,991 | 35% |

| 18 | Tennessee | 3,511 | 1,216 | 35% |

| 19 | Montana | 1,327 | 452 | 34% |

| 20 | Florida | 1,768 | 597 | 34% |

| 21 | Maryland | 790 | 266 | 34% |

| 22 | North Dakota | 1,342 | 446 | 33% |

| 23 | South Carolina | 3,005 | 983 | 33% |

| 24 | Idaho | 1,257 | 409 | 33% |

| 25 | Colorado | 1,686 | 526 | 31% |

| 26 | Nevada | 246 | 76 | 31% |

| 27 | Arizona | 440 | 134 | 30% |

| 28 | Washington | 781 | 236 | 30% |

| 29 | Virginia | 1,479 | 441 | 30% |

| 30 | Louisiana | 2,193 | 623 | 28% |

| 31 | Delaware | 474 | 132 | 28% |

| 32 | Wyoming | 767 | 211 | 28% |

| 33 | Utah | 1,524 | 412 | 27% |

| 34 | New York | 1,145 | 308 | 27% |

| 35 | Caribbean Area | 1,386 | 363 | 26% |

| 36 | West Virginia | 1,549 | 393 | 25% |

| 37 | South Dakota | 1,291 | 326 | 25% |

| 38 | Georgia | 5,749 | 1,416 | 25% |

| 39 | Kansas | 4,071 | 942 | 23% |

| 40 | Kentucky | 3,369 | 755 | 22% |

| 41 | Nebraska | 4,146 | 883 | 21% |

| 42 | Iowa | 4,623 | 980 | 21% |

| 43 | New Mexico | 1,430 | 289 | 20% |

| 44 | Pennsylvania | 2,259 | 456 | 20% |

| 45 | Illinois | 2,133 | 427 | 20% |

| 46 | Oklahoma | 4,541 | 895 | 20% |

| 47 | Missouri | 4,910 | 935 | 19% |

| 48 | Pacific Basin | 111 | 21 | 19% |

| 49 | North Carolina | 2,648 | 468 | 18% |

| 50 | Minnesota | 3,512 | 611 | 17% |

| 51 | Mississippi | 11,436 | 1,932 | 17% |

| 52 | Arkansas | 8,658 | 1,212 | 14% |

[1] United States Department of Agriculture (2021). EQIP – Regular: Number of Applications by State and Contract Fiscal Year, Contract Fiscal Years 2005-2020.

[2] United States Department of Agriculture (2021). CSP and CStP: Number of Applications by State and Contract Fiscal Year, Contract Fiscal Years 2005-2020.

[3] IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press.

[4] United States House of Representatives Committee on the Budget (2021). Budget Reconciliation Basics., https://budget.house.gov/publications/fact-sheet/budget-reconciliation-basics (accessed August 24, 2021).

[5] Crane-Droesch, A., Marshall, E., Rosch, S., Riddle, A., Cooper, J., and Wallander, S. (2019). Climate Change and Agricultural Risk Management Into the 21st Century, ERR-266. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

[6] Natural Resources Conservation Service (2021). Environmental Quality Incentives Program. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/national/programs/financial/eqip/ (accessed August 24, 2021).

[7] Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation. 2021. Anaerobic Digesters. https://dec.vermont.gov/air-quality/permits/source-categories/anaerobic-digesters

[8] Ritchie, M., and Ristau, K. (1987). Crisis by Design: A Brief Review of U.S. Farm Policy. League of Rural Voters Education Project. https://www.iatp.org/documents/crisis-design-brief-review-us-farm-policy (accessed September 2, 2021).

[9] Rosenberg, N., and Wilson Stucki, B. (2019). How USDA distorted data to conceal decades of discrimination against Black farmers. The Counter. https://thecounter.org/usda-black-farmers-discrimination-tom-vilsack-reparations-civil-rights/ (accessed August 26, 2021).

[10] National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (2021). Grassroots Guide to Federal Farm and Food Programs: Conservation Stewardship Program. https://sustainableagriculture.net/publications/grassrootsguide/conservation-environment/conservation-stewardship-program/ (accessed August 24, 2021).

[11] American Farm Bureau Federation (2019). EQIP and CSP Conservation Programs in the 2018 Farm Bill. https://www.fb.org/market-intel/eqip-and-csp-conservation-programs-in-the-2018-farm-bill (accessed August 24, 2021).

[12] Stubbs, M., and Monke, J. (2020). Staffing Trends in the USDA Farm Production and Conservation (FPAC) Mission Area. Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11452 (accessed August 24, 2021).

Thanks for sharing.